Keaton in the USSR: Mysteries of Soviet Film Distribution

Since we're planning to present a copy of Sherlock Jr. preserved in the Gosfilmofond to the world in the near future — and, if all goes well, other treasures too (besides Sherlock Jr., the official Soviet film distribution lineup also included Our Hospitality, Three Ages, and The General, in that order) — let's take a moment to dive into the history of the Soviet fascination with Hollywood in general, and Buster Keaton in particular, to understand what these copies are and how they ended up there.

In many interviews over the years, Buster Keaton delighted in recalling that at one time he even surpassed Charlie Chaplin in popularity in "the most impossible country in the world" — Russia (then, of course, the Soviet Union). This was brought to his attention by the famous movie stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, who visited Moscow in the summer of 1926. Archival press studies reveal some truth to this claim. Just before the actors couple’s visit, following the triumphant Soviet screenings of Our Hospitality in the winter of 1926 and Three Ages soon after, Soviet audiences indeed fell in love with Keaton. Local film critics didn’t merely view his films as good entertainment, but admired them as high art, praising his acting style, subtle humor, and cinematic craftsmanship. However, Keaton also never forgot to note that despite his popularity, he received no financial benefit from it, because the Soviets allegedly used to get a single copy of his film from Germany for $5,000 and then just duplicate it for screenings all across the country. Let’s try to investigate how true this claim might be by delving into the history of Soviet film distribution.

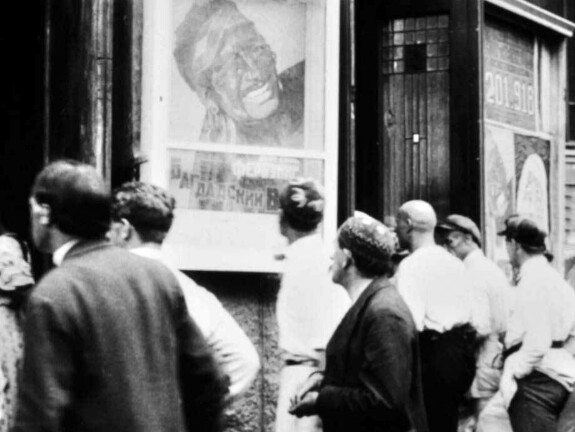

Crowd in Moscow meets Fairbanks and Pickford, 1926

After the October Revolution of 1917, when the Bolshevik Communists came to power, and the Civil War, which lasted almost until the end of 1922, the once-thriving Russian film industry fell into decline. Film studios virtually ceased operations, and in 1920-1921 not a single cinema in Moscow operated for weeks at a time, while most theaters in the provinces closed entirely. The situation began to improve in the spring of 1921, when an economic crisis forced the new government to lift its ban on private enterprise. As a result, state-nationalized cinemas were temporary leased to private operators and began reopening. In Moscow alone, the number of functioning cinemas grew from ten at the end of 1921 to fifty by 1923 (however, even by 1928, the Soviet film market remained relatively small — for example, here you can read Joe Schenсk's analysis of the situation).

Up until the second half of the 1920s, Soviet cinemas predominantly screened imported films, as the revenue from their screenings was crucial for the survival and development of the domestic film industry. Even by 1925 Soviet movies accounted for only 30% of the total film distribution. Reviving local production proved challenging, and audiences were reluctant to watch domestic films. For example, a mid-1920s survey featured a comment from an anonymous viewer who noted a preference for foreign films because "they are more diverse and feature stunt actors, whereas Russian films depict everyday life and constant construction of houses." In the mid-1920s, Hollywood productions enjoyed special popularity, especially those starring Fairbanks and Pickford, as well as D.W. Griffith's films featuring Lillian Gish. Of course, short comedies with Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Max Linder, and lesser-known comedians, such as Monty Banks and the Danish duo Pat and Patachon (Ole & Axel), were also major crowd-pleasers.

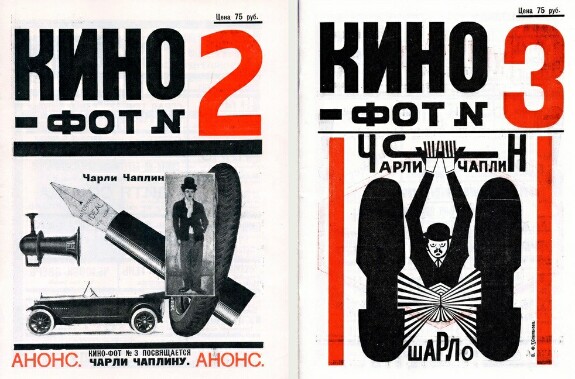

Chaplin on the covers of Kino-Phot Magazine, 1922

However, in the early 1920s, existing channels for importing films had collapsed, and new ones were yet to be established. Initially, foreign films were supplied by private individuals who smuggled them into the country through various illegal means — not only from Europe but also via contraband routes through China and Siberia. Starting in 1922, the legal import and distribution of foreign films in their own cinema networks were handled by a number of recently created private and state organizations, such as Kino-Moskva, Sevzapkino, Kino-Sever and others. In 1923, the state-owned company Goskino joined the effort, aiming to monopolize Soviet film imports, though it ultimately failed to achieve this goal. Meanwhile, Western, especially American companies avoided direct contacts with the Soviet film industry, so films were purchased through different intermediaries via the USSR’s trade mission in Germany (as Buster correctly noted). Mostly rather old and thus cheap movies were sold in bulk through auctions, where Soviet film distribution organizations competed against one another. These bulk purchases frequently did not allow for selecting specific titles, leading to a mixed bag of pictures. The content and artistic quality of these films often drew heavy criticism in the Soviet press, but with no alternatives, they still filled cinemas. Under these conditions, it’s no surprise that pirates still accounted for more than half of Soviet film imports, offering more current and engaging movies that attracted eager audiences.

To address the situation, another state-run company, Sovkino, was established in the summer of 1924, tasked with unifying the whole Soviet film industry under its control. It began operations in March 1925 and was granted exclusive rights to import and distribute films across the entire country (Union republics of Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Turkmenistan maintained partial autonomy), while other companies were required to submit all previously acquired copies to Sovkino archives. Unified imports also helped organize centralized censorship, which had previously been very chaotic, allowing ideologically harmful pictures to reach Soviet viewers. Now, every film was first reviewed by the Sovkino editorial team, followed by a special commission from the Main Board of Film Censorship (Glavrepertkom). If a film was deemed suitable for distribution, it was re-edited — sometimes severely, with entire plotlines removed. It was not so easy to slip through the censorship — for example, in the period from October 1925 to October 1926, only 122 out of 276 imported films reviewed reached the audience. American films were considered both the most attractive to audiences and the most acceptable in terms of content, as it was believed that in them "...the negativity of the content is more than compensated [...] by healthy dynamics, artistic design and technique." Additionally, Sovkino planned to export Soviet movies abroad, and since no global market could compare to the American one, establishing connections with the U.S. film industry was seen as one of the company's key goals.

Sovkino logo

The first (unsuccessful) attempts to restore relations of the United States film industry with the reformed Soviet Russia were made as early as the fall of 1922, before the end of the local Civil War. At that time, Keaton's producer, Joseph Schenck (who was born as Iosif Mikhailovich Sheinker and lived in Russia until he was 14), was planning to travel to Moscow as a part of his European tour. In response to an invitation extended by the Soviet Government, Schenck intended to explore the possibility of not just exporting U.S. films to the USSR, but also establishing a movie monopoly with the participation of American capital. However, after meeting in Berlin with Charles Recht, the official representative of Soviet interests abroad, Schenck changed his mind about visiting Moscow. Upon his return to the United States, he expressed his opposition to cooperation with Russia, citing the fact that the internal conditions there were still not sufficiently stable.

With the establishment of Sovkino, Russia aimed to halt the flow of smuggled films and strengthen its ties with the Western film market by purchasing films directly from producers. In May 1925, the company opened an office in Berlin, followed by another in Paris in June, and an American office on Broadway in October. The office was headed by actor and director Lev Zamkovoy, who actively engaged with the American press, highlighting the immense demand for Hollywood films in the Soviet Union. He also negotiated with studio representatives about buying and selling film, and thanks to his efforts, in December 1926, despite criticism and some censorship resistance, Battleship Potemkin by Sergei Eisenstein was released in U.S. Furthermore, Zamkovoy likely played a role in facilitating the visit of Fairbanks and Pickford to Moscow in July of that same year.

However, Sovkino struggled with acquiring American films. Previously, Soviet distribution companies had purchased limited screening licenses through intermediaries, typically covering only a handful of theaters and ordering just 2-3 copies of each film. These licenses cost roughly 5,000 rubles (~$2,500 at the 1925 exchange rate, which was only half the amount Keaton recalled) and were paid for upfront or on short-term credit. But Sovkino had much grander demands. First, the company wanted copies of the selected films sent to Russia for review by the censorship commission even before a deal was made (and the suppliers were expected to cover all the cost of transporting the copies in both ways). If a film was approved for Soviet audiences, Sovkino would request 16-18 copies of each title while offering only about 2,500 rubles (~$1,250) for a license that allowed screenings across the entire country. Furthermore, Sovkino expected to purchase these licenses on 6-12 months of credit, with payment drawn from profits generated by the screenings. Local distribution companies were now required to rent films from Sovkino, reimbursing a percentage of the licensing cost. Given the rapid deterioration of film stock caused by poor-quality equipment and the inexperience of rural projectionists, Sovkino likely had to duplicate copies from the positives provided by suppliers to expand distribution across the country. Naturally, film producers received no additional revenue from these duplicates. These terms infuriated European suppliers and were entirely unacceptable to American studios, which resulted in Sovkino being unable to secure American films from 1925 to 1928. As a result, the very first official purchase of American films by Sovkino occurred only after Joseph Schenck’s long-awaited visit to the USSR in August 1928, when the company finally acquired five titles (including The General) directly from United Artists and several more from Universal.

Soviet audience in line for a screening of The Thief of Bagdad, 1925

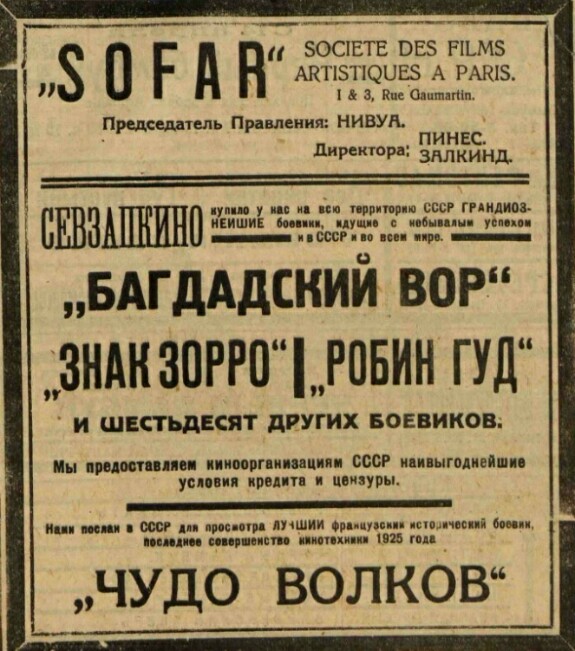

So, how did Soviet film distribution manage to screen three of Keaton's feature films in 1925 and 1926, if Sovkino didn't buy them? Definitely, Sherlock Jr., Our Hospitality, and Three Ages were officially released through Sovkino, as evidenced by their title credits and accompanying promotional materials. However, all three were acquired by another organization, Sevzapkino, a state company based in Leningrad (modern-day St. Petersburg). It had happened in the second half of 1924 — just before the monopolization of film imports and distribution by Sovkino. This acquisition was a part of an exceptionally successful deal for a large batch of foreign films. Through two intermediaries — the short-lived German distribution company Berolina Film and the French SOFAR (Societe des Films Artistiques A Paris, founded partly by Russian émigrés) — Sevzapkino secured a lot of brand-new Hollywood blockbusters, rather than older stockpiled titles. In total, over 60 films from various studios were purchased during this deal, including the newly released high-budget fantasy The Thief of Bagdad, starring Fairbanks, and the film’s massive advertising campaign made Doug a superhero-like figure in the USSR for a few years to come. However, as usual, due to budget constraints, Sevzapkino, acquired a very limited number of copies of each film. Reportedly, even The Thief of Bagdad was screened in Moscow in five theaters, using only three copies.

Announcement of Sevzapkino's purchase of The Thief of Bagdad, Robin Hood, The Sign of Zorro and more than 60 other films with the assistance of SOFAR, 1925

Keaton's situation, as a relative newcomer to Soviet audiences at the time, was likely no better. So, it is entirely plausible that his recollection of the USSR acquiring only a single copy of each of his films and then duplicating them for nationwide distribution aligns closely with reality. Sevzapkino briefly premiered each of Keaton’s films in Leningrad in December 1924, but was soon forced to transfer all of the acquired copies to Sovkino. A year later Sovkino finally launched Keaton’s films into big distribution, first in several major theaters in Moscow and Leningrad, and then throughout the whole country, which briefly turned Buster into a really big Soviet star.

(... to be continued...)

silent cinema

silent comedy

cinema

buster keaton

old hollywood

douglas fairbanks

mary pickford

ussr