"Sherlock Jr." - The Mystery of the Script

As you can understand from the previous post, it was "Sherlock Jr." that became my gateway into the world of Buster Keaton. To this day it remains, along with "The General" (and, in a close third place, "Our Hospitality"), my favorite. This incredibly clever and inventive film still feels so modern that after seeing it, a person, unfamiliar with silent film culture, once asked me in all seriousness if "Sherlock" was a modern stylization of turn-of-the-century cinema. And as befits a detective, this film has the most mysterious production story of all Buster's pictures.

Many books about Keaton mention that "Sherlock Jr." was initially titled "The Misfit" and was inspired by the Broadway play “Merton of the Movies”, the screen rights to which Buster, who saw the production during a visit to New York in the fall of 1922, wanted but was unable to acquire. For example, James Curtis, in the last, most detailed and considered definitive biography of Buster, states that "the impetus for "The Misfit" was almost certainly “Merton of the Movies" and cites this description of the upcoming premiere's plot from Motion Picture magazine (March 1924):

"It tells of a projection machine operator, again a small town hero, who goes to Hollywood to make his fortune and fully becomes a millionaire-producer."

Doesn't sound much like the film we know, does it? There's no hint of "the world's greatest detective", Sherlock Jr., nor the mind-blowing idea of the protagonist entering the movie screen, which has become a hallmark of both the film and Keaton himself — on par with the train crash scene in "The General" and the falling house facade in "Steamboat Bill, Jr." Instead, the announcement actually closely resembles the plot of "Merton of the Movies," where the small-town aspiring actor Merton Gill, a fan of actress Beulah Baxter, heads to Hollywood to become a dramatic film star, only to unwittingly become a hugely successful comedian due to his ridiculous acting. Curtis goes on to describe how "The Misfit" transformed into "Sherlock Jr.":

"[By mid-December] Keaton had been forced to abandon the idea of bringing his character to Hollywood, and a new device had to be found to set the action in motion. In desperation, he returned to a setup similar to the modern story in Three Ages: two suitors for the same girl, one good and one bad. Due to the chicanery of his rival, Buster is unjustly accused of theft and ordered from the house. He must solve the crime to redeem himself, sparkling a burlesque of the detective genre most recently exploited by John Barrymore in Sherlock Holmes. In fact, it was courtesy of the Barrymore release that the film acquired its permanent title: Sherlock Jr."

That is, according to Curtis, the plot involving the rivalry for a girl's heart didn't appear in the movie until mid-December, by which time filming had already been underway for several weeks, and only then it led to the occurrence of the detective theme, conceived as a parody of a recent Barrymore film, to which "Sherlock Jr." also owes its name. However, Curtis doesn't explain what in this case was being filmed before mid-December - and where are any traces of it? What forced Buster to abandon the Hollywood idea in desperation, and, most intriguing, when and how came the idea of merging the two plot parts using the scene of the projectionist getting inside the movie?

In our quest for answers, let's start by tracing the plot's evolution through Hollywood press coverage. Curiously, while Keaton usually didn't hide his plans, during the production of "Sherlock Jr." the plot was "held a close secret." From the very beginning until the premiere, Buster steadfastly refused to reveal anything about the future film's content beyond promising the audience the best and most original stunts and gags. Official shooting began on November 26, 1923, although, according to a letter from Roscoe Arbuckle to Minta Durfee (we'll discuss Roscoe's involvement separately), it actually started quietly at least a week earlier, on November 19, with filming locations scouting and preparatory work commencing soon after the premiere of "Our Hospitality" in San Francisco on November 4.

The film remained untitled until December 8, when the press first time mentioned the name "The Misfit." However, by Christmas, it had been officially renamed, and only then, nearly two months into production, some hints about the plot surfaced in the press—paradoxically, not aligning with the new title. On December 26, the LA Daily News reported that Keaton's next picture would be called "Sherlock Jr.," mentioning a recent location shoot in Sonora (which we'll also discuss in future posts) and being the first to announce that in the new film, Buster "plays the role of a projection machine operator in a hick town, who comes to Los Angeles, captures the screen's most beautiful darling, and then branches out as a producer and manager of a chain of theaters." The LA Times briefly summarized the same story on December 30, and a month later, on January 28, 1924, even embellished it with details, trying to present the upcoming film as a satire on the hot topic of censorship:

“In “Sherlock, Junior” Buster shows the average small-town “board of cinematographic censorship” at work. Two short-haired women as well as long-haired male reformer are on Buster’s board. And, boy, what fights they stage! The Dempsey-Firpo first round was nothing compared to the rows in which Buster’s board of censorship engage. A perfectly harmless motion-picture, after it dissected by this board, is clipped, cut and sheared down until nothing is left of it except the tag reading “Passed by the Hickville Board of Censorship”.

As you can see, this description still doesn't even remotely resemble the familiar parody-detective plot. However, according to the same The LA Times, filming the first rough cut of the movie was completed by February 8, less than two weeks after this description publication date. Judging from a preview report, the version shown at Hoyt's theater in Long Beach on February 19 was already the "Sherlock Jr." we know today, featuring the scene where the protagonist enters the movie screen and the ensuing car chase by bandits, culminating in the gag involving brakes on all four wheels (which actually was a hidden advertisement of a new Buick model).

Four brakes gag

It's very unlikely that the film could have completely transformed in just a couple of weeks of filming, so, it's safe to assume that the stories about censors and Hollywood had little to do with what Keaton was actually working on even when they first appeared in the press. However, these stories, whether intentionally or not, served as a smokescreen for the real plot, which the creators preferred to keep under wraps. This ruse was so effective that the true storyline remained largely unknown until the film's premiere. Even major film magazines, like the Motion Picture cited by Curtis, continued to publish outdated information to the very end. Moreover, some lazy announcement writers, without bothering to watch the finished film or read actual reviews, were still talking about the projectionist-turned-producer and the Hollywood satire even after "Sherlock Jr." hit the screens (one, two, three).

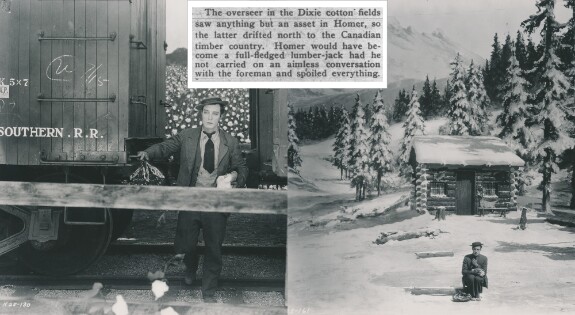

But how did this happen? Did Buster originally plan the plot about a projectionist going to Hollywood and the battle with censors when he started working on "Sherlock Jr."? It seems likely! The key evidence lies in the film's plot synopsis attached to the copyright registration application stored in the Library of Congress. Since 1912, when registering rights, companies sent to the United States Copyright Office not only two copies of the film itself (which were later returned to the owners) but also a text description of the story, which after registration of rights was deposited in the Library of Congress. Judging by the descriptions of other Keaton films preserved in the Library (such as, for example, "The Day Dreams," "Seven Chances," and "Go West"), these texts weren't specially written for copyright registration after the final cut. Buster Keaton Productions usually provided the descriptions prepared for the press books, which were used for announcements and advertising in the press — naturally, well before the films were finished. Since Keaton often worked through trial and error, revising the story during the whole filming and even after previews, the final version of his plots frequently diverged from what appeared in press books and, consequently, in newspapers. For example, the plot synopsis of "The Day Dreams" in the Library of Congress collection refers to the first, three-reel version of the film with a happy ending and Virginia Fox as the leading lady. Similarly, the description of "Go West" includes scenes with Friendless (named Homer Holliday there) traveling south and north, that were presented in the still photos but cut from the final movie.

"Go West" deleted scenes and their mention in the plot synopsis

So, in the case of "Sherlock Jr.", the Library of Congress also received the early plot description prepared for the press book, fragments of which were used unaltered in some articles, and it reads as follows:

“Buster, as the general utility boy of Hicksville's Elite Cinematographic Palace, seating capacity 250, runs the projection machine, sweeps out, polishes up the brass rails and dusts off the instruments of the theatre's two-piece orchestra.

As sweeper and projectionist, Buster is in a continual wrangle with the local censorship board which slashes his films into ribbons three times a week. He indulges in a few friendly arguments with the exhibitor-proprietor on the side.

Buster's girl goes back on him when the town bully and sport plants the pawn ticket for a stolen watch on him and then "finds" it while Buster is at the girl's home.

Thus disgraced, Buster becomes a detective, qualifying for the job by taking a $2.00 correspondence course.

For years Buster has watched Kathryn - "Hollywood's Sweetheart" and filmdom's most famous actress - together with the villainous Ward Crane who continually crosses her path on the screen. He longs to go to Hollywood, pulverize the villain and make Kathryn his own.

One night when Buster's desire to go to Hollywood has reached its feverish climax he becomes entangled in the film which oozes out of his projection machine. He is wafted through the projection booth aperture and dissolves right into the action on the screen.

Buster arrives in Los Angeles which he believes to be a live town. He is disillusioned however, when at the stroke of midnight, he is thrown out of a big hotel by two police commissioners and their cohorts. Rescued by Kathryn he embarks on a screen career.

San Francisco millionaires, in order to show up the peanut politicians of Los Angeles, finance the former motion picture operator, and he becomes one of the most famous producers of the screen. Buster even ups his score with the blue-law politicians by running them out of office and then marries the screen's most pampered darling - Kathryn.”

The most striking difference between this plot and the "Sherlock Jr." we know is, of course, the absence of the "world's greatest detective" character and the whole "investigation" storyline. The projectionist here really battles censors and, in the second part, heads to Los Angeles, where accidentally becomes a famous producer. Notably, he is drawn to Hollywood not by career prospects but by his love for "Hollywood's Sweetheart" (the role in the description reserved for Kathryn McGuire - a detail that will become important later). Contrary to Curtis's claim that Keaton had to hastily use the story of rival suitors and the stolen watch as a replacement for the Hollywood plot, these elements are present in the prototype plot simultaneously - as is the key scene in which the hero crosses into the movie screen, although its description doesn't quite match what we see in the final movie (and we'll come back to that too).

Buster Keaton himself, in interviews during the 1950s and 1960s, never mentioned "Merton of the Movies" as an inspiration for "Sherlock Jr.," nor did he ever talk about a plot involving a projectionist who ends up as a producer in Hollywood. Moreover, he outright denied Curtis's claim that "Sherlock Jr." has any connection to a Barrymore film (Brownlow, 1964). Instead, Keaton repeatedly stated that "the reason for making the whole picture" was "just that one situation: that a motion picture projectionist in a theatre goes to sleep and visualizes himself getting mixed with the characters on the screen" (Gillette and Blue, 1965) and that "from there on we laid out that story" (Brownlow, 1964), indicating that the starting point for the entire plot development was exactly the scene where the hero transitions into the film on the screen.

As noted by the Los Angeles Evening Express in an article about the upcoming premiere, Buster "has long had the idea" of a "picture within a picture" “in the posterior part of his cranium.” Indeed, the theme of the connection and merging of cinema and dreams was not new for Keaton. Two years prior, he had already explored the idea of a film-within-a-film, equating cinema with dreams, in the short film "The Frozen North" (1922). There his character, much like the projectionist in "Sherlock Jr.," falls asleep in a theater and dreams of himself as a bad cowboy - the (anti-)hero of the western he was watching. In "Sherlock Jr.," Buster took this concept even further, showing the very moment of the hero physically crossing the boundary of the screen and transferring into the movie. The idea of a character going into or out of a film screen was not entirely new, and Buster could have got the inspiration even in the vaudeville times. For example, in 1914, John Bunny, the most popular comedian at the time, whose work Buster possibly followed, opened the three-hour show "Bunny in Funnyland" with a short film, in which Bunny rushed to the theater for his performance. When the clip ended at the appropriate moment, the curtain rose and the comedian ran out to the audience as if coming off the screen, still out of breath.

In the film-cartoon "Gertie the Dinosaur" (also 1914), which reportedly had already inspired Keaton for an animated brontosaurus scene in "Three Ages" (1923), animator Winsor McCay would step into his cartoon and interact with the animated Gertie on the screen:

Entering the screen in "Gertie the Dinosaur" (1914)

However, before "Sherlock Jr.," no one had shown the transition with such convincingness, inventiveness and mastery — the idea and technical execution of the scene were truly unique. Keaton was immensely proud of this episode, stating "that was an invention" and that "every cameraman saw that picture more than once, trying to figure out how in the hell we did some of that" (Brownlow, 1964). Emphasizing the pivotal role of the transition scene and other camera tricks within the film-dream for creating the entire "Sherlock Jr." plot, Buster noted, "the reason we started off on that story is because I had one of the best cameramen in the picture business, Elgin Lessley" (Franklin, 1958).

Elgin Lessley, 1922

What is interesting, in the early plot description there are no indications that the transition occurs in a dream. If we assume that the provided synopsis doesn't just leave it out, the plot suggests that the protagonist is pulled into the screen in “reality,” that is, the story is fantastical, and the entire narrative involving the projectionist-producer and his relationship with "Hollywood's Sweetheart" unfolds in the film-within-a-film, which was not conveyed in the press. In the interview with Robert and Joan Franklin, Keaton indirectly confirmed that the idea to use a dream came to him not from the beginning, but only after considering material of prepared ideas for gags together. He realized that with such unrealistic elements — where the transition to the screen scene itself was perhaps the most surreal — crafting a believable story would be impossible:

“I can’t do it and tell a legitimate story, because there are illusions and some of them are clown gags, some Houdini, some Ching Ling Foo. It’s got to come in a dream.” (*)

_______________________________________________

(*) There seems to be a mix-up with this interview segment. Curtis in his book quotes Keaton as follows:

(*) There seems to be a mix-up with this interview segment. Curtis in his book quotes Keaton as follows:

“... I laid out some of those gags. And the technical man that builds the seats, I showed him how I have to get them built for the things I had to do. [When] we got that batch of stuff together, [Lessley] said, ‘You can’t do it and tell a legitimate story, because there are illusions and some of them are clown gags, some Houdini, some Ching Ling Foo. It’s got to come in a dream.”

This implies that it was Buster’s operator, Elgin Lessley, who explained to Keaton the impossibility of using magical gags in reality, and who supposedly suggested the idea of a projectionist dozing off in his booth and entering the film. However, if you listen to the original, Keaton actually says there:

“...I got that batch of stuff together, and... said: ‘I can’t do it and tell a legitimate story...’”

BusterKeaton_vk

Buster about Sherlock Jr. idea (1958).mp3

0:00

0:26

Lessley is not mentioned at all in this part of the interview. A similar mistake appears in Kevin Sweeney's 2006 transcription, where the “technical man” is presented as the advisor on impossible gags and storytelling, as well as the originator of the sleeping projectionist idea instead of Lessley.

_______________________________________________

With the start of making the features, Buster became very attentive both to the fact that the events shown were possible, even if unlikely ("once we started into features, we had to stop doing impossible gags and ridiculous situations. We had to make an audience believe our story"(Franklin, 1958), and to the storytelling in general. Meanwhile the “Hollywood” subplot from the synopsis not only bears too obvious resemblance to the story of “Merton of the Movies” (which was being filmed around the same time and released in the fall of 1924, six months after “Sherlock Jr.”), but it also has little to do with the first part of the projectionist's misadventures. This kind of structure was common in two-reel shorts, where the first half of the film could barely connect to the other half (“Haunted House”), however, it hardly suited the narrative framework of a feature film. Perhaps it prompted Keaton and his team to not only shift film-within-a-film action into a dream, but also to fundamentally alter its content.

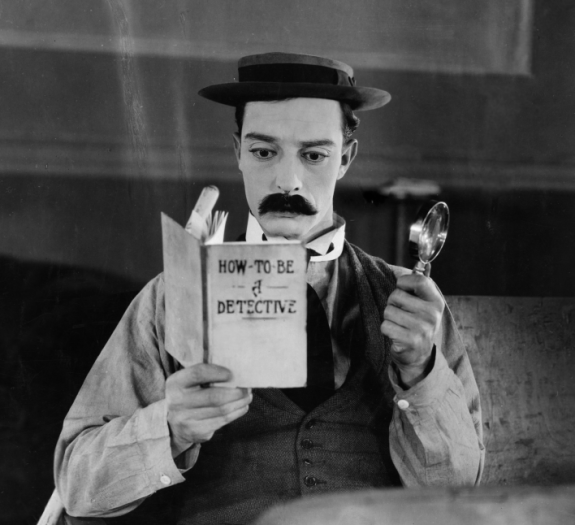

Worth noting that the idea that eventually blossomed into the projectionist's detective dream is already present in the early plot description. After a story with the stolen watch, Buster's character, presumably seeking to restore justice, buys a $2 correspondence detective course, though this plot point doesn’t get any development at that stage. It’s possible that the course originally found its way into the story thanks to “Merton” again — in the play, Merton Gill studies correspondence acting course before heading to Hollywood. Years later, in the pilot episode of the second season of “The Buster Keaton Show,” titled “Detective Story” (1951), which recycled many ideas from “Sherlock Jr.,” the correspondence detective course appeared in its rightful place (though it had increased in price to $5, and now included a dog). In the original 1924 film, however, all that remains of it is a book titled “How to Be a Detective,” which the projectionist studies in his very first scene. There his desire to master the detective profession arises not from a need for self-defense but is revealed from the very beginning. It provides an opportunity to use Keaton's beloved storytelling technique — mirroring, when the transformation of “those characters on the screen into my characters at home” (Brownlow, 1964) in a dream beautifully intertwines the two parts of the film’s narrative: the real and the imagined.

Characters transformation in "Sherlock, Jr."

So, taking into account all that has been said above, it is possible to propose the following hypothesis for the creation of the "Sherlock Jr." script. Breaking his own principle of story building — where the focus was primarily on crafting the start and the finish (with the middle taking care of itself) — Keaton, according to his own words, this time started with the climactic idea of the film-within-a-film and the protagonist's dive into the screen (as we will see further, there are some evidence that filming actually began with this scene). To frame the transition scene, Buster and his gagmen devised a plot structure, that in the first part incorporated a familiar template, prevalent in Keaton's previous work (“Three Ages”): the main character (provincial projectionist) competes for the hand and heart of a girl against a more successful but treacherous villain.

In the second part they initially reworked the storyline from a Broadway production that Buster enjoyed, by sending the hero to the Hollywood directly through the silver screen. Perhaps it happened because the draft script for the movie was prepared in a hurry: in early November of 1923, just a couple of weeks before the official start of “Sherlock Jr.” shooting, Keaton's team was still planning to rent a ship and jump straight from “Our Hospitality” into “The Navigator," but it looks like they couldn't find a suitable vessel, so had to switch to another plan. Then, while filming progressed on the entering-the-screen episode and the first part of the story with the girl and the watch, the second part was completely rewritten; the “mertonesque” journey to Hollywood transformed into a parody detective story set within a dream, so by mid-December of 1923 at the latest, the narrative had taken on familiar elements and the film soon adopted its well-known title. By this point, the press had already received and circulated an outdated plot description — but, as can be inferred from the reluctance to comment on the film's content, Keaton was perfectly fine with this situation. The film was initially built around one unique technical idea and a series of original cinematic tricks, so misleading announcements could be even useful to keep everything in secret and prevent the theft of the innovative material by spies from other studios.

However, reworking the script on the fly was far from the only problem that Buster and his team had to face while working on this very challenging movie. Replacement of the main actress, problems with Roscoe and endless cuts and rework - we'll talk about all this in the next posts.

buster keaton

silent cinema

silent comedy

sherlock jr.

Johnr Roberts

When the "four-wheel-braked" car pulls up suddenly, it appears that a model is used (and a wire or string to achieve the sudden stop), judging by the large bubbles being made by the released body (and the fact that it skims along, rather than plowing headfirst) on a water's surface that's too unbroken to be that of a regular lake.

Dec 29 2024 11:40

1

BusterKeaton_vk

Johnr Roberts, yes! The very moment of the car jump into the lake, of course, is filmed in miniature - like, for example, the destruction of the dam in Our Hospitality

Jan 23 13:15