The King of the Champs-Elysees

or Buster Keaton's adventures in Paris

Ninety years ago, on January 10, 1935, the Paramount cinema in Paris hosted the premiere of Buster Keaton’s first French film, The King of the Champs-Élysées (Le Roi des Champs-Élysées), which also marked his first feature-length project after being fired from MGM almost two years prior. Today, this film is considered one of his best “talkies,” despite being made during a deeply troubled period in Keaton’s life, hastily, with limited funding, and with a crew he didn't know. Moreover, his voice was dubbed—something Keaton vehemently opposed—and in the film's final frames, breaking his cardinal rule, he even flashed his bright, truly Hollywood smile, a sight movie screens hadn't seen since 1920[1].

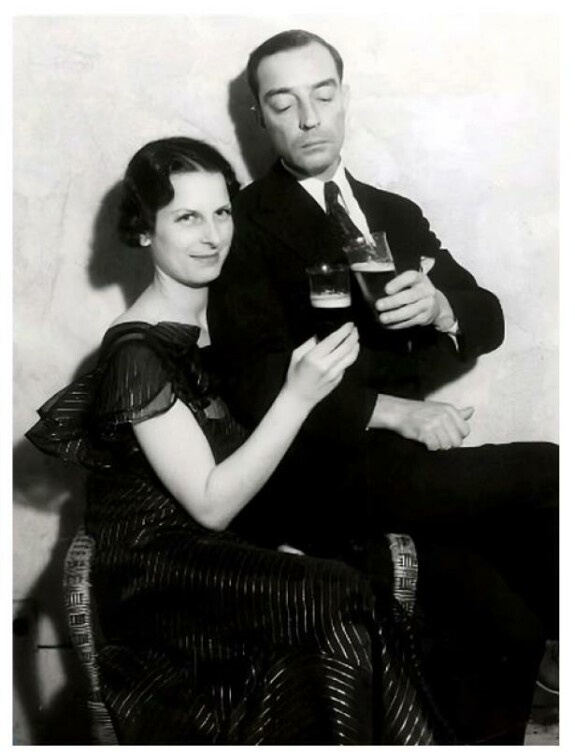

Buster, his smile and Paulette Dubost

None of these unfortunate circumstances endeared the film to Keaton himself. He always considered The King of the Champs-Élysées a failure, saw “nothing good” in it, and years later strongly advised Raymond Rohauer, his devoted fan and business partner, against wasting time and money searching for a print of the picture. However, compared to Keaton's sound films made at MGM, The King stands out favorably: it has a certain charm and Parisian atmosphere (the Arc de Triomphe, narrow streets, and old buildings play their part), boasts a number of beautiful shots and successful gags, and Keaton’s character here is once again imbued with the touching vulnerability and resourcefulness of his earlier characters from classic silent films.

Beyond the smile, what truly sets this film apart is the fact that Keaton plays two roles: the traditional good-natured but ill-fated hero, Buster Garnier, and the ruthless American gangster, Jim le Balafré (Scar), who has escaped from prison. Keaton had always been drawn to the idea of playing a villain, or better yet, two characters at once—one good and one evil, much like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde[2]. He had expressed the idea of such a dual role as early as the spring of 1921, when he was planning to use multiple exposure in The Playhouse. Watching how different Keaton can be on screen, and how Jim le Balafre’s facial expressions and physicality differ from the timid, down-on-his-luck actor Buster Garnier, even when they are wearing the same prison uniform, is the film's main attraction, making one regret that Keaton didn’t get to do something similar during his golden age, and that Hollywood never recognized his villainous potential.

To understand how Keaton ended up in France, we need to look back at a couple of difficult years. After being fired from MGM in February 1933, Buster sank into a deep bout of drinking, culminating in a spontaneous trip to Mexico. During this trip, Mae Scriven, a nurse hired after his divorce from Natalie Talmadge to keep an eye on his drinking (but who became romantically involved with her famous patient instead), suddenly announced to the press that they had been secretly married in Ensenada, Mexico, a couple of months earlier. Buster, still quite inebriated, played along, which sparked scandalous headlines in the press around the world[3]. In the summer of 1933, Keaton tried to start anew by founding an independent production company, Flamingo Film, in Florida with his friends, screenwriter Lew Lipton and director Marshall Neilan. Alas, this plan failed due to lack of funding and difficulties with filming in Florida, so the feature-length comedy The Fisherman, about an eccentric millionaire's attempts to win the heart of a Spanish belle, was never completed[4]. This latest setback led Keaton to a new spiral of desperate drinking, an unsuccessful (for this reason) attempt at a live performance tour, and a real formal marriage to Mae in Ventura, California. To top it all off, at the end of 1933, he signed a contract for six short films with a little-known independent producer, Jesse Weil.

Buster and Mae

Weil, a former press agent who had tried to break into producing in the late 1920s, was known by the time he met Keaton for little more than lawsuits against the screenwriter Ralph Spence over alleged breaches of contract, a complaint from a starting actress about a $75 theft, and a single completed film, Maid to Order (1930), starring the popular drag queen Julian Eltinge (the release of Maid to Order, however, was also plagued by a lawsuit from a defrauded investor). Unsurprisingly, Weil's contract with Keaton turned into another disaster: Buster soon discovered that Weil had neither the funds nor the means for filmmaking, and that Weil's entire activity boiled down to attempts to resell his contract. In January 1934, Keaton sued Weil, demanding to be released from the patently fraudulent agreement, which also forbade him from working anywhere else for its duration. However, Weil, experienced in such matters, filed a countersuit, accusing Keaton of wrongfully terminating the contract without objective reasons, and won the case, forcing Buster to pay damages amounting to an astronomical $108,444.

In that same January, Keaton, who had been without steady work for almost a year by that point, finally signed a real contract for six short films with Educational Films, but this did little to improve the situation. In addition to the hundred-thousand-dollar debt to Weil, Buster was burdened with obligations of almost the same amount for shares in San Diego real estate, once purchased on credit together with the Schenck brothers, Louis B. Mayer, and other Hollywood magnates, but which had depreciated during the Great Depression; unpaid taxes for 1932–1933; alimony to Natalie Talmadge; and other debts, the total of which exceeded $300,000 against Buster's total assets estimated at around $12,000[5].

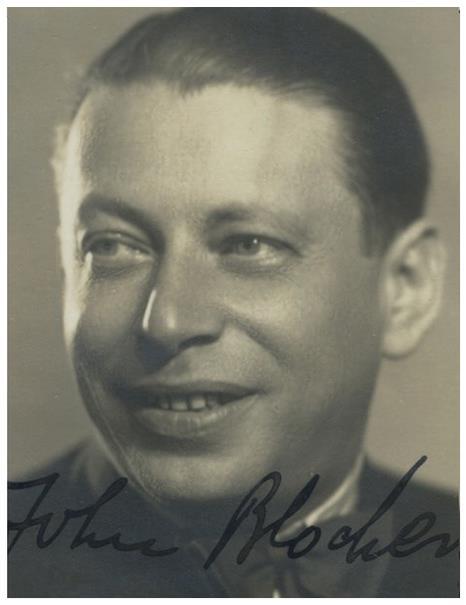

John Blochert

Therefore, when a man named John Blochert, posing as a producer from Vienna, arrived in Hollywood in early May 1934[6], Keaton was desperately in need of money. Blochert, representing his newly founded French company, Les Films Margot, offered him a handsome sum for the time: $30,000 for four weeks of filming a feature-length comedy in Paris. But his main condition was a contractual obligation for Keaton to smile or laugh at least once in the film. Blochert intended to build the film's advertising campaign around this unique event and use it to secure funding. Keaton, burdened by his debts, had little choice but to compromise his signature persona, which had maintained unwavering seriousness for almost fifteen years, and the contract was soon signed. Upon returning to Paris, Blochert plastered the rented Les Films Margot office on the Champs-Élysées with eye-catching posters promising a “super-production with grand sets,” in which it was boldly stated that audiences would “see Buster Keaton laughing on screen for the first time.” He also placed similar colorful announcements in the French Cinematographie magazine.

An advertisement for the film in La Cinématographie Française of May 26, 1934

Keaton, having finished his current work on the Educational shorts, set off for Europe in early June. Buster's agent, Leo Morrison, who handled the contract negotiations, for some reason failed to secure either an advance from Blochert or arrangements for how his newly minted star would get to the filming location. Therefore, Buster had to sell his remaining World War I Liberty Bonds for $350 to buy tickets for himself and Mae on the California Express, an orange freighter bound from Los Angeles to London, where the Keatons planned to catch a flight to Paris. Unlike luxury liners that reached the foggy shores of England in five days, the freighter traveled via the Panama Canal and, having left Los Angeles on June 14, didn't arrive in London until July 7. The trip was a complete disaster: three days after departure, Keaton, by his own account, suffered food poisoning from some bad shellfish and spent almost the entire voyage confined to his bed. He also managed to injure his hand with a table that overturned during a storm. Mae, however, enjoyed the opportunity to travel and even spoke to the press on her husband's behalf, calling their journey a “long honeymoon trip.”

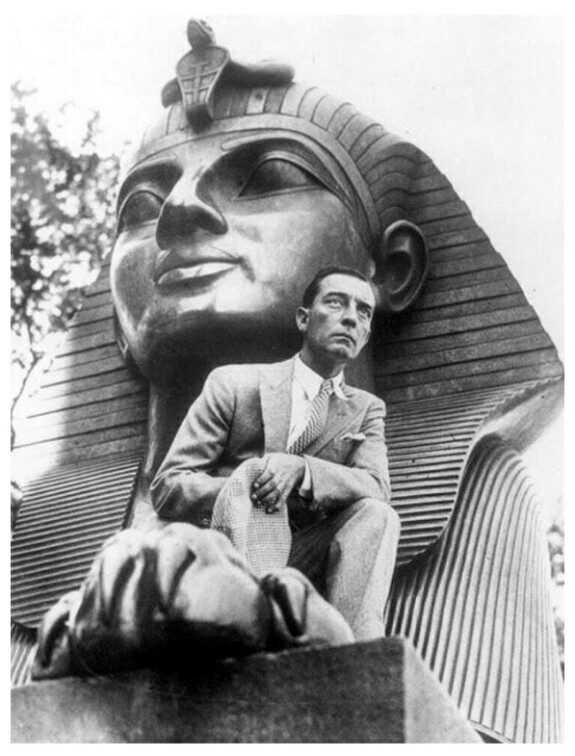

Two Sphinxes, London, July 8, 1934

Buster hardly shared her enthusiasm. A journalist who visited him in London on the day of their arrival found Keaton in bed at his Savoy Hotel[7] room, groaning and looking “twice as sad as he is in the films.” Buster told him that he hoped to get up only the next day and kept his word: the next day he strolled with Mae through the Embankment Gardens and took the famous photograph with the London Sphinx—a creature with whom he was so often compared due to their shared legendary impassivity. The couple spent a few more days in London until Keaton's condition improved, though Buster still felt so unwell that he even refused whiskey, preferring diluted lemon juice.

On July 13, the eve of Bastille Day, Buster and Mae flew from London to Le Bourget. They missed their flight and took the next one, so almost no one was there to meet them at the airport, except for Blochert himself and his partner, the well-known French impresario Nicholas Behars, as well as a couple of photographers. Blochert had promised journalists that he would arrange a press conference that same day, where they could ask the famous guest all their questions, but nothing of the sort happened. Buster, under the protection of his manager Hank Hartman, who represented Leo Morrison in France (Morrison had intended to follow Keaton to Paris but changed his mind), successfully avoided any attempts to interview him, citing fatigue, and retreated to a hotel, the location of which was kept a strict secret.

From left to right: Nicholas Behars, Mae Keaton, Buster Keaton, John Blochert at Le Bourget Airport, July 13, 1934

At first Keaton apparently settled into a two-room suite at Claridge's, a luxurious historic hotel on the Champs-Élysées, not far from the Place de l'Étoile and the Arc de Triomphe. While waiting for filming to begin on July 30, he diligently avoided the press and reportedly even pretended to be his own manager on the phone when some nosy journalists managed to get his number. By 1934, Keaton's fame in France had not yet faded, and reporters were trying to sniff out the smallest details about the life of the visiting Hollywood star. The L'Intransigeant newspaper, using connections at the hotel, told the readers that for breakfast, Buster preferred scrambled eggs, bread and butter, grapefruit, coffee, and sometimes a pot of honey (by the end of July, he was clearly feeling better, and his appetite had returned, giving the French press reason to joke that his two main flaws were "politeness and gluttony"[8]); that he devoted half an hour to physical exercise every morning (and the maid allegedly even saw him walking around the room on his hands), after which he spent a lot of time on his ablutions, managing to create a “terrible mess” in the bathroom. Furthermore, the newspaper told that Keaton preferred to dine at a nearby restaurant, sometimes strolled incognito along the Champs-Élysées, surprising passersby who nevertheless recognized him with his contagious laughter (he even participated in the public festivities on July 14, shooting at a target range and trying other attractions), and accompanied his wife on shopping trips.

The newspaper also reported that Keaton spent a good part of the day practicing his French with a phonograph and coming up with gags for the upcoming film. Indeed, although the script for The King was prepared by the German writer Arnold Lipp, announced by Blochert from the very beginning and possibly having arrived in Paris with him, and the dialogue was to be written by the French playwright, screenwriter, and film director Yves Mirande, it was Keaton who was named as the sole gagman for the picture. Furthermore, although Buster didn't know French[9], he had a good phonetic memory, was used to making films in different languages at MGM, and was a staunch opponent of dubbing, insisting that his voice belonged to him as much as his face[10]. So, it was initially planned that he would voice his own characters, who, in full accordance with his ideas about sound comedy, were intended to have as few lines as possible, only in the most necessary places.

However, by the end of July, it became clear that the situation with The King was beginning to resemble the stories with Flamingo Films and Jesse Weil: it turned out that John Blochert and his Les Films Margot had no funds for filming. A certain foreign investor of Blochert's, who supposedly planned to finance the film's creation, encountered problems transferring money to France and backed out of the idea. Blochert had managed to offer the distribution rights for the film featuring Buster Keaton's smile to a number of countries, including Spain, Italy, Holland, Scandinavia, Hungary, Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, but the foreign distributor, Transat-Film, wisely refused to pay for filming with funds from pre-sales, so as not to end up in debt if the picture never saw the light of day. As a result, Blochert disappeared[11], and the film's production came to a halt. By the planned start date of filming, a studio in Joinville, belonging to Paramount, the film's French distributor, had been rented, but all obligations under contracts with the already hired actors and crew were suspended, the music and lyrics were not ready, and Yves Mirande had not even begun writing the dialogue.

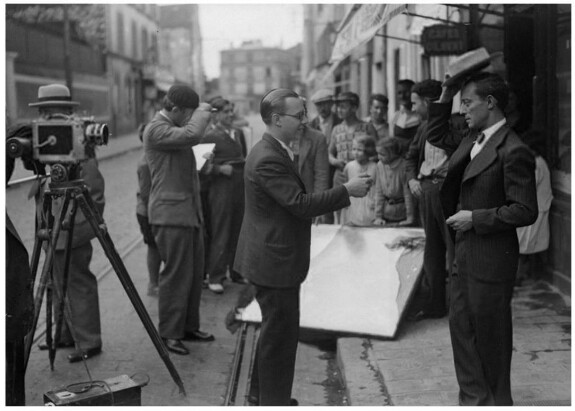

Buster on the set of The King of the Champs-Élysées

The situation was saved by the German company Nero-Film, which took over the film's production in early August (possibly thanks to the efforts of Nicolas Behars, who had worked with them before). However, now all the preparation had to be done in a desperate rush: the cast was finalized in a few days, composer André de Badet had to create the gangsters' anthem in just a few hours the night before filming, and the script was being reworked right on set. A separate difficulty lay in the fact that the filmmakers and actors literally spoke different languages: director Max Nosseck, a longtime friend of screenwriter Lipp[12], who was also confirmed for his position immediately after Blochert managed to persuade Keaton to star, knew only German; their main star knew only English; and the rest of the crew and troupe knew only French. Therefore, everyone had to communicate with the help of translators – the assistant director René Montiss and Keaton's manager Hank Hartman – which did not simplify or speed up the work in any way.

Nosseck – an energetic man half a head shorter than Keaton – directed, according to the press, "sweating and writhing as if he were directing a team of rescuers on a destroyed railway line," and created an extremely nervous atmosphere on set, reshooting take after take. Buster's pronunciation, not always perfect, but often satisfactory to his French colleagues, constantly seemed incorrect to Nosseck, and he demanded that the lines be spoken again and again, reworking the hastily devised dialogues by Mirande so that it would be easier for Keaton to reproduce them, and still remained dissatisfied. Work on the film began on August 6 and, according to the recollections of editor Jean Delannoy, took only 12 shooting days. Closer to the end of filming, it was decided that Buster's voice would still be dubbed.

Mirande and Keaton also didn't get along very well. Buster, who spent his free time apart from the crew, seemed to the Frenchman "arrogant and complacent," and his unwillingness to smile – foolish. Despite the contractual obligation, Buster did not back down from his position; when a reporter from Le Matin, who visited the set, saw Keaton laughing off-camera and once again asked why he was famous as a man who never smiled, Buster replied that, in his opinion, "in order to make people laugh, you don't have to laugh yourself," and the source of comedy "lies in observing the absurd side of everything in the world."[13]

Yves Mirande and Keaton don't like each other

However, even though Keaton mostly kept to himself in an unfamiliar environment, he made a very positive impression on the rest of the film crew. The stagehands admired his simplicity and unpretentiousness, marveling at the fact that, despite his star status, Buster "didn't act like a star" towards them. When he was in a good mood, he joked around with the crew members and put on small shows for onlookers, for example, alternately transforming the cane in his hands into a golf club, with which he would hit an invisible ball, a drum major's staff, or an acrobatic dancer's prop. Keaton still tried to avoid journalists, but when they did manage to corner him on set, he spoke to them calmly and amiably: he said that he loved France, that he hadn't seen any recent French comedies, so he couldn't judge them, that the atmosphere at the studio was very friendly and the co-stars were charming (he especially liked Madeleine Gitty, who played his mother – Buster reported that she was "very funny" and even made him laugh two and a half times). On the other hand, he did not hide his view that the French film industry still "lacked order and method" and that for the creation of truly large-scale films in France, local studios still needed to expand and improve.

His drinking remained a major concern for those around him. Editor Delannoy recalled that, as a precaution, even the bars in the vicinity of the Joinville studio, near which Keaton had rented a villa for the days of filming, were strictly forbidden to serve him. However, Buster found ways to get alcohol, for example, by ordering whiskey directly to his room at Claridge's before shooting began. Nevertheless, if Keaton did drink, no one noticed it was affecting his work or professionalism this time. He patiently repeated scenes as many times as Nosseck deemed necessary, even if the work process dragged on well past midnight ("I'm used to it"), and impressed casual observers with his transformation the moment the cameras started rolling. Journalists wrote that, although looking at Keaton off-set, "it's hard to believe that this is one of the greatest comedians in cinema," he was not only a comedian, "but first and foremost an artist – it's enough to see him at work to be convinced of this,"[14] or that "even a banal scene with his participation involuntarily arouses interest, since its creator invests in it a passion for his craft, authenticity, and subtle observation of human nature, which allows him to find in the heat of the action an unexpected, funny, and effective gag, suddenly deepening the scene’s meaning."[15]

Filming on the streets of Paris

The French press, before filming began, describing Keaton's work on the gags for the upcoming film, reported that he had supposedly brought with him to Paris a filing cabinet made of reinforced steel, completely waterproof and fireproof, in which, recorded on cards, all the gags he had used in films since 1917 were systematically stored. The gags in the filing cabinet were supposedly sorted by the situations in which they could be applied and by the props used, and that with its help Buster invents new gags by combining old ones. Indeed, some scenes in The King in a modified form quote his past works – for example, a series of dark jokes about the protagonist's suicide attempts is reminiscent of Hard Luck (1921), and a ruined performance had already been seen in Daydreams (1922), Spite Marriage (1929), and the sound film Speak Easily (1932). Keaton himself indignantly rejected such assumptions, stating to one interviewer that he couldn't imagine who could have thought that he came up with gags sitting in his office, since the comic effect would not work if the gag was not created for a specific situation, and that he found all the ideas on the set. However, to another journalist who asked where he found humor, Keaton, "smoking a cigarette rather wistfully,"[16] replied with a concise phrase, perhaps key to understanding equally his work and worldview:

"In life."

By August 24, filming of The King was completely finished. Despite promises of a "super-production with grandiose sets," after all the upheavals and delays, the film was shot not only hastily but also cheaply – so much so that for the night chase scenes of the bandits after Buster, Nero-Film used extra footage from Fritz Lang's previous year's film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), released by the same company. Buster's voice was indeed dubbed, but obviously also in a rush: not only does the same dubbing actor voice several characters (for example, the vegetable seller speaks with the same voice as Buster), and his high timbre is as far as possible from Keaton's hoarse bass-baritone; the dubbing was done so carelessly that in several places it is missing, and Buster delivers his lines himself. Moreover, his dubbing actor, apparently, was also not French, speaking with a very strange accent to the French ear[17], and reviews upon the film's release noted that "when Buster speaks, it sounds unnatural" and "his voice and the dubbing do not match". It was clear that, contrary to the hopes placed on The King even in the States, the film was unlikely to restore Keaton's former popularity. In addition, Buster later recalled that instead of the promised $30,000 he received only half[18], so it is not surprising that his experience working in France disappointed him.

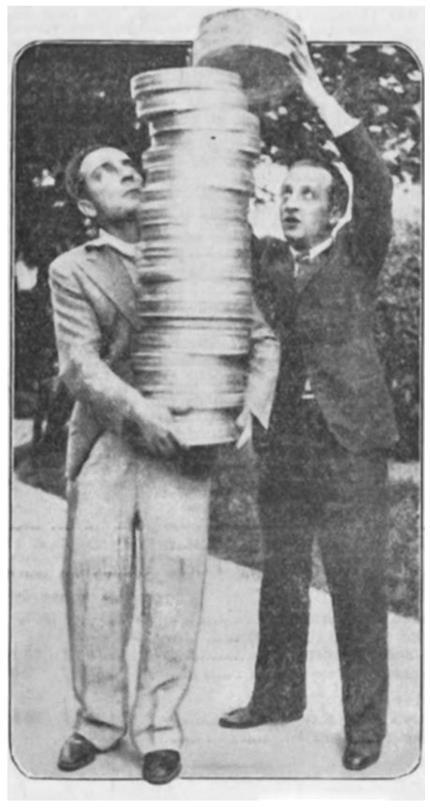

Keaton, director Max Nosseсk and the fruits of their labor

When filming was finished, he moved from the villa in Saint-Maurice back to the Champs-Élysées, this time to a studio apartment at 6 Rue Jean-Goujon. Although he still had time, he flatly refused an offer to shoot a short film in addition to The King[19] and preferred to spend the last days of August in nature, camping in the Rambouillet forest, which he greatly enjoyed ("Magnificent scenery!"). After completing The King, Keaton initially planned to return to the States for the Educational shorts, but during his stay in France, his plans changed. At the end of July, British film producer Frank Zeitlin flew to Paris to negotiate work in London, and in mid-August, Buster signed a contract for future live performances with a silent sketch at the Viennese variety theater Ronacher. The Austrian plans were not to come to fruition, but on September 3, Buster flew from Paris to Croydon, planning to start work on his first British feature film, as yet unnamed. However, preparation for filming took longer than Keaton expected, so he and Mae, with the money received for The King, managed to travel around Europe, visiting Monaco, Venice and the Villa d'Este in Italy, and even Basel in Switzerland. On September 22, Keaton returned to London to begin work on The Invader – a remake of the unfinished The Fisherman for the company of aspiring producer Sam Spiegel. But what came of this is a completely different story, and we will tell it another time.

The text was prepared based on French publications L'Intransigeant, Comœdia, Le Jour, Excelsior, Aux écoutes, Paris-soir, Marianne, La République, La Liberté, Cine-magazine, and others, which extensively covered Keaton's work in the summer of 1934, as well as a number of Dutch, English, and American publications and archival documents.

A digitized Czech 35mm copy of the movie from the Gosfilmofond archive is available here (with English subtitles): https://youtu.be/kbObOsII_50

__________________________________________________

Notes

Notes

[1] The last time Keaton smiled on screen was in The Saphead, released in 1920.

[2] Keaton expressed the desire to play this duo and to take on the role of a villain in general, for example, in an interview with Irvin Allen in 1945.

[3] Keaton’s divorce from Natalie had been finalized less than a year prior, which under the law of the time made him a bigamist and could have led to criminal prosecution.

[4] Keaton returned to this plot twice: in the English feature film The Invader (1935) and the Columbia short Pest from the West (1939).

[5] In the summer of 1934, while already in Europe, Keaton got rid of the main part of his debts through bankruptcy proceedings, conducted by hired lawyers in his absence.

[6] Blochert arrived in New York on the "Majestic" on May 1st.

[7] Keaton recalled in his autobiography that upon arriving in London, he was surprised to find a check for $1,000 in his name, sent by his former producer and brother-in-law Joe Schenck – funds supposedly obtained from the sale of the remaining equipment from Buster Keaton Studio. Keaton remembered nothing about any equipment, but the money turned out to be very useful, allowing him to settle comfortably in Europe.

[8] Buster’s appetite was a subject of humor in the American press as well. Starting in the early 1920s, newspapers covered Natalie’s (futile) attempts to put him on a diet, ran ads for grills and candies in his name, and reported on his struggles to resist his favorite treats during the filming of Battling Butler (1926), when he decided to diet on his own. With a mix of humor and amazement, they detailed his eating habits—whether in the MGM cafeteria or at French restaurants—describing how, in one sitting, he could devour a cocktail, snails in brandy, champagne, a massive platter of frog legs, more champagne, and finally a lobster prepared American-style as the grand finale. In the mid-1920s, one magazine even published a playful poem about Hollywood stars, neatly rhyming “Buster Keaton” with “who is ever eating.”

[9] In 1952, during the time his performances at the Medrano Circus in Paris, Keaton reported that his entire French vocabulary was limited to words and expressions that he had memorized during his first visit to France at the age of 23 during World War I: "Would you like, mademoiselle, good, not very good, I would like to go to Pigalle, to walk, chocolates, bad Germans" (Pigalle is a well-known red-light district in Paris).

[10] Keaton's interview to Cinémonde magazine, n° 94, August 7, 1930.

[11] John Blochert, the man who first persuaded Buster Keaton to smile on screen, actually was an editor from Berlin, who decided to try his luck in the French film industry, moving to Paris with his wife Margot and naming his production company after her. In February 1936, a little over a year after the failure of The King, he left Paris for Czechoslovakia with 15,000 French francs. There, Blochert almost immediately attracted the attention of the police by attempting to poison himself, presumably due to financial difficulties, but he was saved. After that, Blocher worked as a publication’s distributor for the Prague state printing house, and then as a collector of materials for the "Czechoslovak Biographical Encyclopedia." He attracted the attention of the police several more times, getting into debts and receiving advances for work he did not complete, and in November 1938 he was suspected of espionage. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Nazi troops in April 1940, Blochert, after a repeated suicide attempt, was arrested by the Nazis and placed in the Jewish department of a Prague hospital. He died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp on March 1, 1944.

[12] In 1920, Lipp and Nosseck, who were then seventeen and eighteen years old, made short films together, with Nosseck as the actor and Lipp as the director.

[13] Le Matin, August 17, 1934.

[14] Christian Godefroy for Paris-soir, August 17, 1934.

[15] Le Matin, August 17, 1934.

[16] Louis Atlas for The Chicago Tribune and the Daily News, August 11, 1934.

[17] The strange accent of the dubbing actor who voiced Keaton in The King of the Champs-Élysées, and the study of Max Nosseck's voice in later projects where he played bit parts, makes one think that possibly Nosseck did the dubbing himself.

[18] At least in his autobiography, Keaton mentions the sum of $15,000.

[19] The plan for Keaton to make an English-language version of The King in 1935 also failed to materialize.

buster keaton

old hollywood

old cinema

comedy

silent comedy

paris

1930s